A group portrait of surrealists and their heroes.

Although ‘Macho’ may not be the first word that comes to mind when we think of Dali or Magritte, The Surrealists of the 20th Century ruled the art world with ultimate machismo.

The surrealist style forces an artist to be macho, to assume more power than possible and show it off. Surrealism is the hardest painting form to be good at. Not only does a surrealist have to have a perfect eye, but a good surrealist has to have good storytelling skills without having access to film or sequence. A surrealist really just gets one chance, one painting, to impress everybody. Light, shadow, time - all of these things must be understood until they can bend absolutely.

While monumental surrealists stay fresh in our popular imagination, a couple of painters in the movement were largely forgotten. Kay Sage and Yves Tanguy together had some of the most innovative surrealistic work, but, they fell by the wayside. Here is why.

A classic Tanguy painting looks like this:

The figures of Tanguy resemble toys scattered across a desert expanse, an expanse like the wasteland of the mind, where certain events and people stand out amidst the noise of averages. Tanguy probably mattered more as a cutting-edge artist during the 1960s and 70s, where surreal abstraction was new, and where writers like Edward Abbey threw him a gracious reference here and there. Thanks to Abbey, I still can't see photos of Monument Valley without thinking Tanguy.

Tanguy’s biggest flaw in connecting with an audience was that he never went so far as to reference Jungian archetypes, myths, or actual historical events directly within his paintings. He had an audience, but it couldn’t hold onto him. It didn't get him.

He could really paint, he could cast a believable sheet, bestow convincing glows across varying surfaces. He embraced the Bretonian surrealistic style and brings his viewers into a deeply abstract world, but a world nonetheless.

The title of this bad boy is "Mama, Papa is Wounded." These are things happening in a place, right?

While a comparison of artists doesn’t seem fair, Salvador Dali and Yves Tanguy were born at nearly the same time, Dali in 1904, Tanguy just four years earlier in 1900. Tanguy was a centurial child, being born on January 5th of the new Century.

Dali ran a specific kind of surrealism that made smart people smarter and awed everyone else. Instead of looking at a Dali painting and feeling utterly lost in an alien Monument Valley, it’s easy to make out a couple figures resembling humans, or that a clock is melting. Dali shows us a melting clock, and we say, Hey, a melting clock, time is weird, I get it. You can see and believe a melting clock, but you can’t scry what these are:

It is a lot of stones in a river I guess?

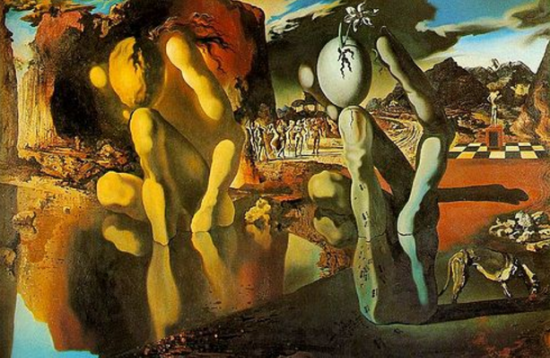

Tanguy doesn’t even throw us a clock. Even if a viewer of Dali has no familiarity with Greek mythology, the paintings still invite curiosity given their various starting points. Who, or what was Narcissus? These questions can lead a contemporary, tech-enabled viewer down the hallways of a somewhat rewarding Google chase. In Dali’s day, who knows what it led to. Maybe an understanding of these paintings were only for the lucky and limited educated class, and The Metamorphosis of Narcissus (below) was just as inaccessible as any Tanguy.

Ok, Dali, right on, it's Narcissus looking at himself, then he turns into stone with ants crawling all over him. Cool, I get it.

A tour guide at the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida could tell you more of the nuances of each Dali painting, slowly piecing together each anecdotal easter egg until the nonsensical-seeming Dali... makes total sense.

It’s really quite exciting to fully understand any Dali painting. It's like solving a quadratic equation for the first time. Dali’s paintings involve us in a great mystery, turning us into a badass art investigator, while the paintings of Tanguy lock us out forever.

Don't know. No clue.

Tanguy didn't seem to want understanding. He didn't want to tell a verbal story that had been told before. He wanted to say something else, but I don't know what it is. He brings us as close as possible to an impossible reality.

Kay Sage was as good a surrealist painter as Tanguy, and though Tanguy and Sage were married, they were correct in never wanting their work to be shown together. Their paintings do not directly converse, at all. Sage was a bit closer to Dali's oeuvre in that she brought people/places/things into her work:

Okay Kay Sage, I see you.

Both Kay Sage and Yves Tanguy aren’t parodied or as referenced as much as other surrealists today, because, well, they weren’t as famous without having that Dali style of storytelling. They met, they married, Yves avoided the army, and they both wound up in the United States. In Connecticut of all places. This was probably the weirdest (worst) possible place two surrealists could be in the 20th Century.

What is remarkably sad about the Tanguy/Sage marriage was that once Tanguy died, Sage spent her life championing this work. It was through this championship of her late husband's work that Sage’s own work was forgotten, then remembered after her own death with renewed scholarship.

And, now that Surrealism as a movement is complete in its lifecycle, these two are the most transcendently pure surrealists that nobody knows about. Sage was a power surrealist who understood complex feelings and made her own stories. Tanguy was the ultimate surrealist because nothing he built started as real, but it crosses the finish line into reality. It exceeds the finish line.

As for what 'Mama, Papa is Wounded' means, nobody will truly ever know.